Ioanna Sakellaraki photographs the last Greek mourners

In her series The Truth is in the Soil, London-based Greek photographer Ioanna Sakellaraki explores the practice of mourning, through her individual story with death. A graduate in photography at the Royal College of Art, her serie looks back at the last community of traditional Greek mourners. Committed to feign grief at funerals, this rite opens up a new way for the photographer to experience personal mourning, which began 4 years ago, while offering identity work.

With a diploma in journalism and urban and cultural studies, you decide to study photography. How would you describe your personal connection to it ?

My photographic ideas revolve around memory and loss and are strongly connected with my homeland Greece which has an archetypical aura and ambiguous personal importance. My images suggest a constructed space of fantasy and loss within the magical potential of transformation and fiction the camera allows. Photography for me has been a slow-paced journey.

How did your Greek cultural heritage influence you and lead you to produce this series of images, released in 2019, The Truth is in the Soil ?

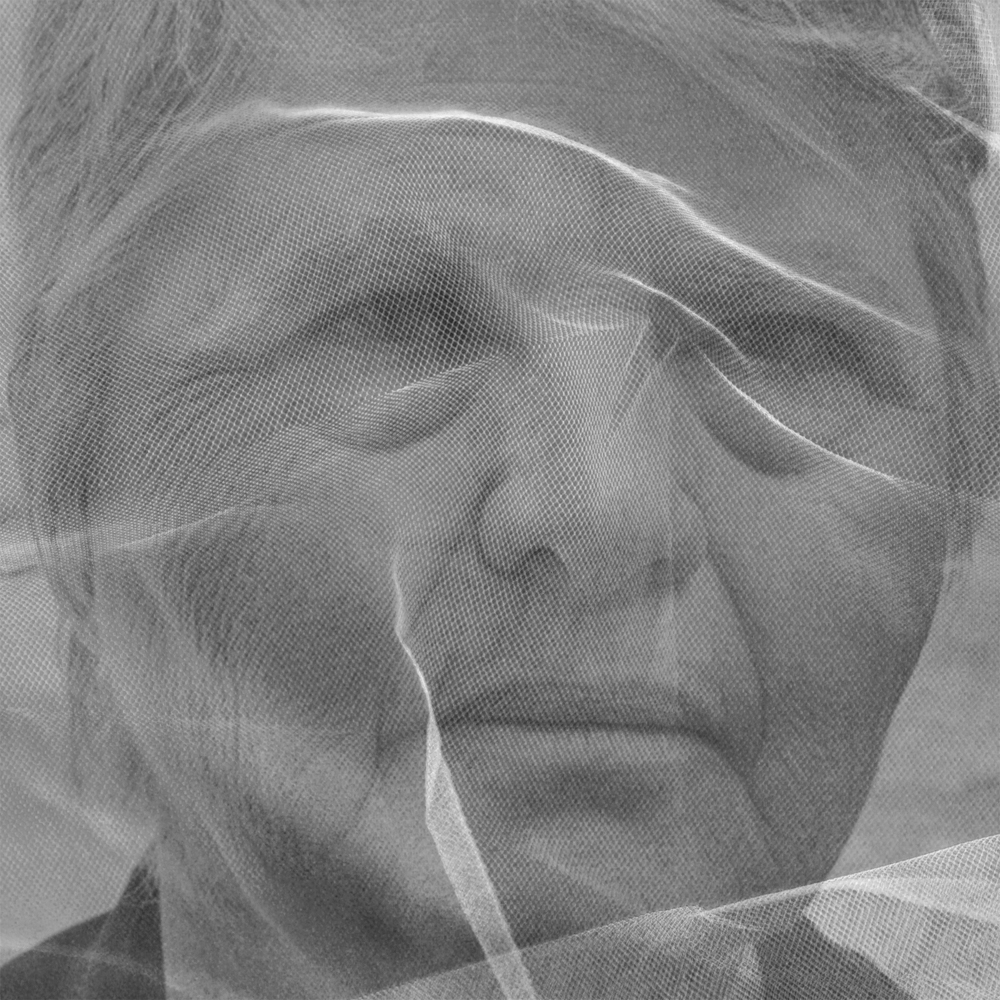

The series started evolving four years ago, when the death of my father sparked a journey back home and the exploration of traditional Greek funerary rituals. Endeavouring to further understand my roots, I aimed to look at how the work of mourning contextualises our modern regimes of looking, reading and feeling with regards to the subject of death in Greece today. Photography transformed itself into a question of becoming through loss and made the passageway within a liminal space of absence and presence. As the project advanced and while inspired by the origins of ancient Greek laments, I dwelled within traditional communities of the last female professional mourners inhabiting the Mani peninsula of Greece looking for traces of bereavement and grief. My personal intention for realizing this project has been the impossible mourning of my father that is yet to come while making this body of work that contemplates around fabrications of grief in my culture and family. The series has been kindly supported by The Royal Photographic Society Postgraduate Bursary Award I received in 2018 which set a structure with regards to the research and realisation of the series from very early on.

What does death and the dead look like, entities that hover in your series of images?

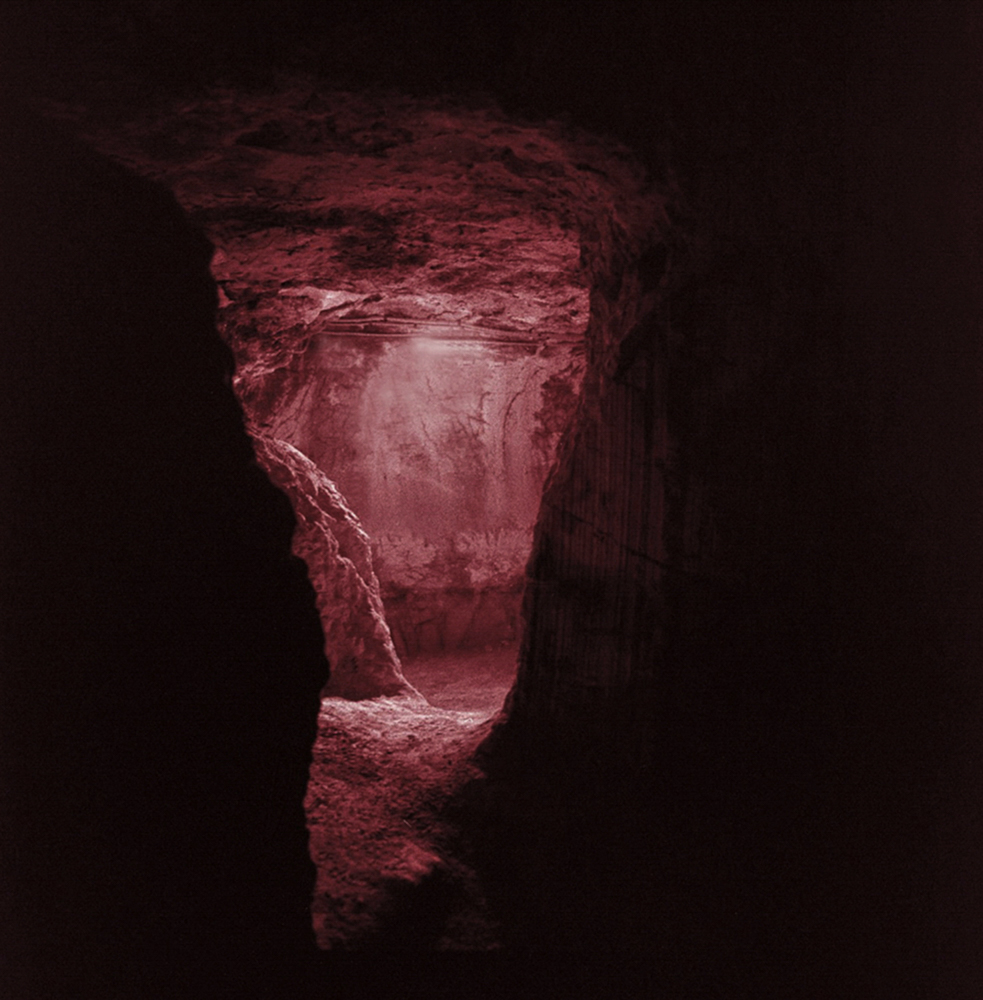

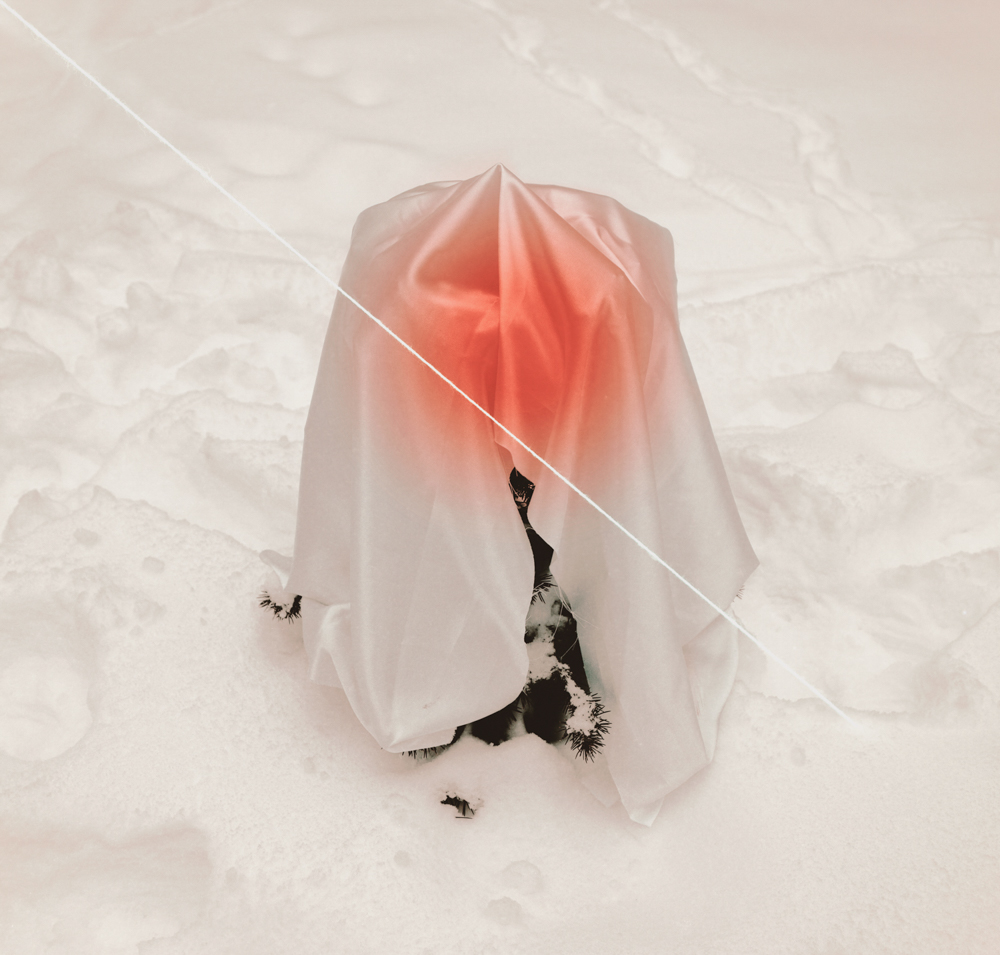

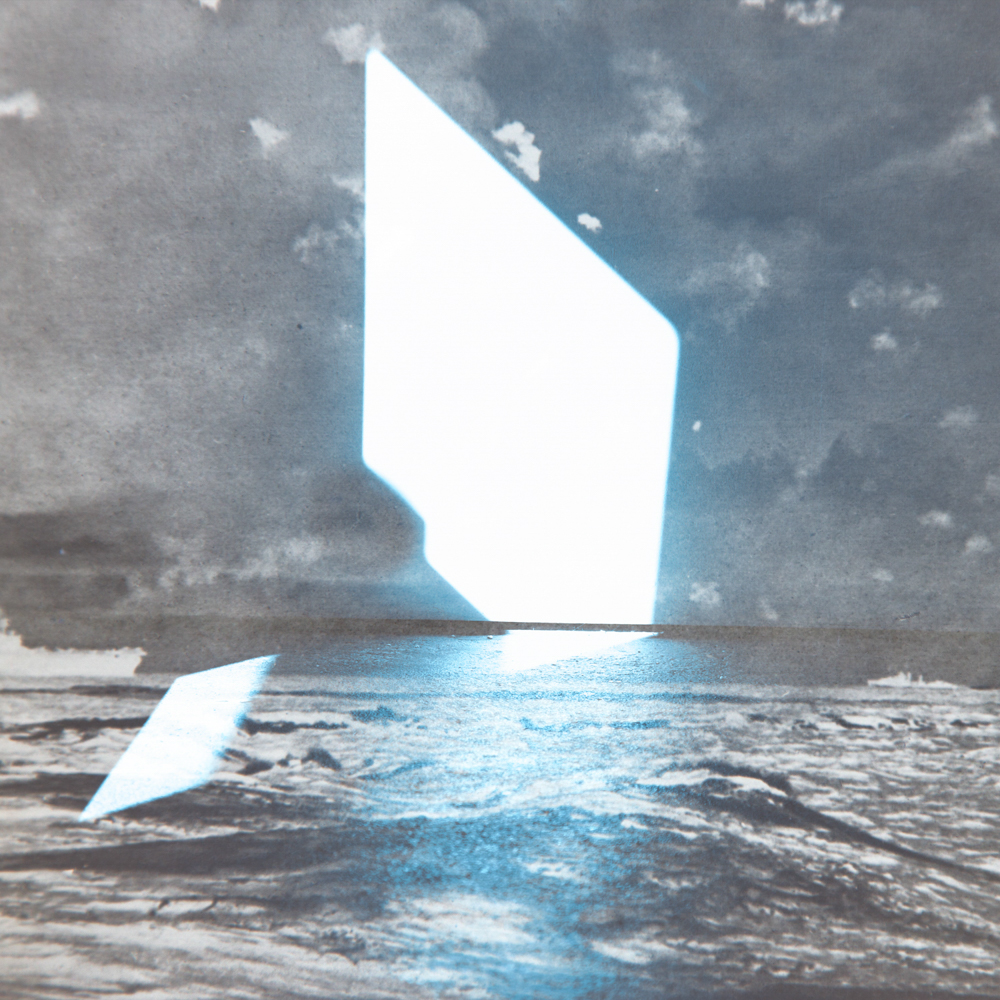

Making a work about grief requires a journey through memory and memory loss. I wanted to talk about what is lost; parts of memory that were reconstructed just like the image of a lost person is in our minds, after he is gone. Whatever we remember forgetfully is a possibility, a fiction. This is how a photograph itself works, within its very own nature, by capturing what is forever futural and already past. Also, my intention of speaking about death rituals was all about how one experiences the spirituality in them and that does not necessarily happen by documenting what happens during them. So, I worked hard on finding ways for these images to tell something further than their subjects, create a nowhere that is here; a space where death can exist. I wanted to let loss happen where the image finds its condition but disappears into it. Through my images, I do not aim at moving towards a surer word in which photography justifies its existence as an art form and medium but rather break bonds that unite the images with the world as seen, detach them from their origin and create a new visual language around the way they are experienced.

Why is death a theme intrinsically linked to your photographic work ?

In my work, I approach death as an open-ended cultural enigma with both subjective and objective interpretations, using my images as passages between sheltering something from death and establishing with death a relation of freedom. I use symbols of the origin as my starting point; what is unknown to us but not completely foreign, to speak about death as a force eating away the visible. The image becomes a rend subsisting by itself and resting upon itself like an organ of time. Something like a shelter; a guardian of becoming. I am always perplexed by how photography as a medium replaces absence with an imaginary presence and how images have the power to make things appear; things that are always deferred and absent others. I see the image as a form through which everything passes, a space where time seeks to be freed. In my practice, I am seeking to develop a language of thought emerging as some type of fiction, becoming all together an impossible image; it can only exist in doubt of its own being and it cannot be fully formed but after its very death.

Ioanna Sakellaraki’s website: ioannasakellaraki.com

© Ioanna Sakellaraki, The truth is in the soil